In the world of motion pictures, Thomas Edison is usually credited with producing the first movies. His “kinetoscopes” were standard arcade fixtures as early as 1895. As was often the case with Edison, his innovations were built on the foundations of inventors before him. The cornerstone of this foundation is Eadweard Muybridge, one of the first pioneers of the motion picture. Eadweard Muybridge is most famous for the moving image, ‘A horse in motion’.

The Motion Picture

To capture motion on film a photographer must produce a series of still images that can be viewed sequentially at high speeds. If the images are viewed at greater than fifteen frames per second, the eye can no longer distinguish individual photos. The images are blurred together by the brain, thus simulating motion. Artists of the early 1800s used this principle – called the persistence of vision – to simulate motion with drawings. The simulator was a device called a Zoetrope. It consisted of a whirling drum with viewing slits through which the viewer could watch a series of drawings spin by. The rapid spinning of the drum combined with the careful alignment of the slits created a sensation of movement. Eadweard was the first person to create a series of photographs that were suitable for this kind of use.

A Horse Named Occident

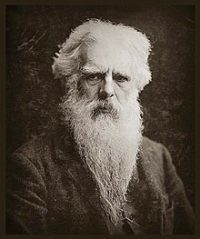

Eadweard Muybridge was born in 1830 in Kingston-upon-Thames England, named Edward James Muggeridge. By the time he was twenty-four he had moved to California and changed his name, focusing on photography as a trade. In the late 1860s the US government commissioned Eadweard to create a photographic survey of the Pacific Coast. While his primary interest in animal biomechanics and physiology was unfulfilled by such landscape portraits, his photographs of Alaska and the California coastline attracted the attention of a man who would become Eadweard’s patron for the next twenty years. California governor Leland Stanford was curious about his horse, Occident. He wanted to know if all four hooves were ever off the ground at the same time while Occident galloped. He hired the photographer whose landscape photographs had impressed him – Eadweard Muybridge.

In 1872, Eadweard created a system of twelve cameras, each with a tripwire, to photograph Occident galloping down the track. With each camera shooting in rapid succession, Eadweard hoped to catch the horse completely aloft in mid-stride. The experiment failed. With slow shutter speeds and exposure times, all that emerged from the darkroom was a very blurry image. Soon after, despite a keen motivation to perfect this photographic form, Eadweard’s experimentation with motion photography temporarily halted.

Improvements and Success

In 1874, Eadweard was put on trial for murdering his wife’s lover. Although acquitted, he spent the next several years abroad. Those years were not wasted however, because while traveling he improved the shutter speed of his cameras to 1/2000th second exposure time. This refinement was pivotal to his future successes, and in the development of all high speed motion photography.

In 1879, with these improvements Eadweard succeeded in creating a sequence of photographs that proved that all four of the horse’s feet were at some moments simultaneously airborne. For some reason such news created a furor that swept through the sporting and equestrian press. Eadweard published the complete series of photographs in many magazines. One reader recognized that these pictures could be used in the zoetrope drums that had long been used with drawings. Finally, the true usefulness of these sequential photographs of animals in motion was revealed.

100,000 Photographs

Inspired by the success of the horse series, Eadweard created many more biomechanical studies, including men jumping and cartwheeling. To further assist the sense of simulated motion, he combined various innovations of the time and invented a viewing machine he called a Zoopraxiscope. This early projector relied on the same principal as the Zoetrope, but added a powerful light, transparent film and a projecting lens. The photographs spun rapidly on the periphery of one disk while in front, spun another disk with carefully spaced viewing slots. The slot isolated the image, projecting it for only an instant, until the next image and slot aligned, and then the next, creating the illusion of motion.

These basic movies were so inspiring and revolutionary, the University of Pennsylvania provided Eadweard with large amounts of financial backing. He traveled throughout the world lecturing on the lessons he had learned about animal locomotion. By the time of his death in 1904, Eadweard had amassed over 100,000 photographs of animals. He also published two separate studies of locomotion, Animals in Motion, and The Human Figure. Three years later an employee in Edison’s lab, William K.L. Dickson would create the first camera and projector using long strips of transparent film spooled continuously by a system of cogs and sprockets – the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope. However it was Eadweard’s scientific vision of capturing motion on film that enabled this later comercial innovation. Eadweard Muybridge inspired a powerful art form and initiated an entire era of educational, political and entertainment photography.